Walk into any online baseball card community and you’ll eventually encounter a recurring conversation: breakers always seem to pull the best cards. The pattern appears too consistent to be random chance – a breaker opens a case and miraculously lands multiple autographs, rare parallels, or the coveted 1-of-1 superfractor. Meanwhile, individual collectors who purchase boxes at retail often walk away disappointed. This perception has sparked one of the hobby’s most persistent debates. Are breakers simply opening more product and benefiting from the law of large numbers, or does something else explain their seemingly endless string of premium pulls?

The question matters because breaking has transformed from a niche activity into a multi-million dollar cornerstone of the modern hobby. Thousands of collectors now participate in breaks rather than purchasing sealed products themselves. The business model depends entirely on trust – trust that the breaker opens products fairly, distributes cards accurately, and doesn’t manipulate outcomes. When collectors suspect that breakers might have access to information about which boxes contain the best cards, or worse, that card manufacturers might be “feeding” breakers premium products, the entire ecosystem faces a crisis of confidence.

This article explores the breaking phenomenon and examines both sides of this contentious theory. We’ll investigate why so many collectors harbor suspicions about breakers’ uncanny luck, consider the legitimate explanations for their success, and analyze what this debate reveals about transparency and trust in the baseball card industry.

What Are Baseball Card Breaks?

Breaking refers to the practice of opening sealed baseball card products – typically boxes or cases – on livestream video while distributing the cards to customers who have purchased “spots” in advance. Instead of buying an entire box for several hundred dollars, a collector might pay $20-$50 for a specific team. When the breaker opens the product, any cards featuring players from that team go to the customer who bought that spot.

Several break formats exist in the hobby. Team breaks divide all 30 MLB teams among participants, with each buyer receiving cards from their selected franchise. Random team breaks work similarly, but teams get assigned randomly after all spots sell. Personal breaks involve a single customer purchasing all spots and receiving every card from the product. Division breaks split the product by AL East, AL Central, NL West, and so forth. Hit draft breaks take a different approach – the breaker opens the product first, then participants draft the hits in a predetermined order based on their spot purchase.

The economic model creates accessibility. A hobby box of high-end Topps Chrome might retail for 300 dollars and contain eight packs. A collector who only wants Yankees cards can instead pay 30 dollars for a team spot and receive any Yankees pulls from that same product. They avoid spending hundreds on teams they don’t collect. The breaker, meanwhile, sells 30 spots at 30 dollars each and generates 900 dollars in revenue from opening three boxes that cost 300 dollars each. The breaker profits from the markup, while participants gain affordable access to products they couldn’t otherwise afford.

History of Breaking

Breaking originated in the mid-2000s through recorded shows by New Jersey card dealer Rick Dalesandro, who went by Dr. Wax Battle, opening boxes on camera as part of recorded events. The practice started small, with dealers filming box openings primarily for entertainment rather than as a formal business model. Early breaking videos served as marketing tools for card shops, giving potential customers a preview of what they might pull if they visited the store to buy products.

The concept evolved gradually as internet bandwidth improved and streaming platforms made live video accessible to small businesses. By the late 2000s and early 2010s, some dealers began selling team spots in advance and shipping cards to remote customers. This transformation turned breaking from passive entertainment into an active participation mechanism. The practice exploded in popularity during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021, when many hobby shops closed to the public and breaking allowed shop owners to continue generating revenue as viewers purchased products without traveling to physical stores.

The growth during this period also stemmed from a lack of live professional sports, as collectors sought alternative ways to engage with the hobby while games were postponed or cancelled. Breaking filled the void left by absent sports, providing regular scheduled events where collectors could experience the excitement of pulling rare cards. The format proved particularly appealing during lockdowns because it combined gambling-adjacent thrills with social interaction through livestream chat.

Breaking has since become a dominant force in the hobby ecosystem. Major card manufacturers now explicitly market certain products toward breakers, creating boxes with team-heavy configurations or guaranteed hits that make breaking more viable. The infrastructure has professionalized as well, with dedicated breaking software, escrow services, and standardized rules governing how breaks operate.

How People Get Involved in Breaks

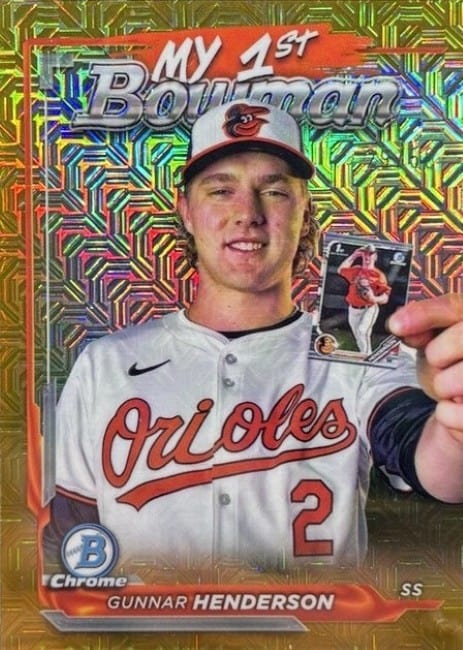

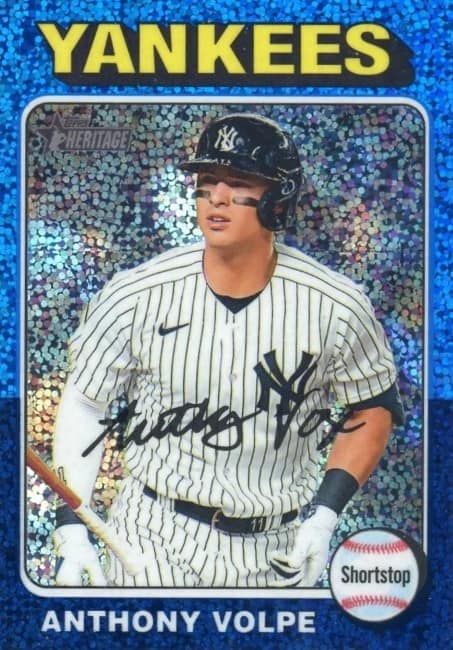

Most collectors discover breaking through social media platforms or hobby forums where breakers advertise upcoming events. Major breakers maintain presences on Instagram, Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube, announcing break schedules and showing highlight clips of major pulls. The visual nature of breaking – watching cards get revealed in real-time – makes it inherently shareable content. A breaker who pulls a rare Mike Trout autograph will post that clip everywhere, attracting new potential customers.

The buying process typically works through dedicated websites where breakers list their inventory of upcoming breaks. A collector browses available products, selects a break format they prefer, and purchases a spot. Payment happens upfront before the box opens. Most breakers use random number generators to assign teams fairly in random breaks, often streaming the randomization process to prove its legitimacy. After the break concludes, the breaker ships cards to each participant, usually within a few days.

Many collectors start with cheaper breaks to test the waters before committing to expensive spots. A $10 random team in a retail blaster break provides low-risk entry. If the experience proves positive and trustworthy, collectors might graduate to $100 spots in hobby boxes or $500 spots in premium products. Breaking appeals particularly to team collectors who would waste money buying complete boxes just to acquire cards from their favorite franchise. A Dodgers collector would rather pay for guaranteed Dodgers content than gamble on products where most cards feature other teams.

The social element also drives participation. Breaking creates community through shared experiences – multiple people simultaneously rooting for hits, celebrating great pulls, and commiserating over disappointing boxes. Regular customers develop relationships with specific breakers, returning to the same shops because they enjoy the personality and presentation style. This loyalty reinforces the business model, as satisfied customers become repeat buyers who trust the breaker to operate fairly.

The Theory: Breakers Get the Best Cards

The central conspiracy theory argues that breakers possess unfair advantages allowing them to consistently pull better cards than individual collectors. Several versions of this theory circulate through the hobby, each with slightly different mechanisms but the same fundamental claim: the game is rigged.

Hot Cases From Manufacturers

The strongest version alleges that card manufacturers deliberately provide breakers with “hot” cases or boxes containing above-average hit rates. Under this theory, companies like Topps or Panini recognize that breakers serve as powerful marketing channels who showcase products to thousands of viewers. By feeding these influencers premium boxes, manufacturers ensure their products look more appealing than they actually are. A breaker who pulls three autographs from a box advertised to contain two creates positive buzz that drives retail sales. Individual collectors who later purchase the same product at card shops encounter normal statistical distribution and pull fewer hits.

Insider Information

A milder version suggests breakers don’t receive deliberate preferential treatment, but do benefit from insider information. Perhaps breakers maintain relationships with distributors who tip them off about which case numbers contain better collation. Or maybe breakers receive advance copies of products before official release dates, allowing them to identify patterns in how manufacturers pack hits. This information advantage lets breakers select the best cases while selling off the weaker ones to uninformed buyers.

Volume & Selection Bias

Another variant focuses on volume and selection bias. Breakers open so many cases that they naturally encounter the best hits that exist in any product’s print run. They film and promote these exceptional pulls while downplaying or not publicizing the many average boxes they open. This creates the illusion of constant success when in reality their hit rate matches anyone else’s, but their visibility amplifies the perception of luck.

Fraud

The most extreme version involves outright fraud – breakers pre-searching products, resealing boxes after removing hits, or staging fake breaks with planted cards. While this represents actual criminal behavior rather than manufacturer complicity, collectors who have lost faith in the ecosystem sometimes assume such fraud happens regularly.

Why Collectors Believe Breakers Have Advantages

Several compelling observations fuel suspicion that breakers enjoy unfair advantages over regular collectors. These patterns, while not proof of wrongdoing, provide enough circumstantial evidence to sustain doubt in many collectors’ minds.

Consistency & Overdelivering

First, the sheer frequency of premium pulls creates legitimate questions. When a breaker consistently hits multiple autographs, rare parallels, and superfractors across different products and manufacturers, probability seems insufficient as an explanation. While large sample sizes naturally produce more hits, collectors notice that some breakers appear to beat expected odds by significant margins. A product with stated 1:200 pack odds for a specific parallel shouldn’t regularly yield multiple copies per case when a case contains only 192 packs. Yet collectors document instances where certain breakers defy these published odds repeatedly. The pattern suggests either manufacturing quality control issues or something more deliberate.

Business Incentive

Second, the business incentive structure encourages skepticism. Breakers profit directly from appearing to offer good value. If customers believe a particular breaker consistently delivers strong hits, they’ll pay premium prices for spots in that breaker’s breaks. A breaker charging $40 per team spot instead of $30 generates an extra 300 dollars per break in revenue. The financial motivation to secure better-than-average products creates obvious temptation. Even if breakers don’t actively cheat, they have strong reasons to cultivate relationships with distributors who might provide favorable treatment.

Disappointing Retail Purchases

Third, collectors who purchase retail products frequently report worse results than what breakers demonstrate on camera. This asymmetry feels unfair even if it reflects selection bias rather than actual manipulation. A collector might watch a breaker open Topps Series 2 and pull four autographs from a hobby box, then buy that same product at their local card shop and pull only one autograph. The manufacturer’s stated odds might guarantee only one autograph per box, making the breaker’s result anomalous and the collector’s result normal. But the collector remembers feeling deceived by the breaker’s demonstration. This perception, whether accurate or not, erodes trust.

Lack of Transparency

Fourth, the lack of transparency in the supply chain enables suspicion. Individual collectors don’t know where breakers source their products, what relationships they maintain with distributors, or whether they receive special pricing or allocations. Card manufacturers don’t publish detailed information about how they distribute inventory or whether certain dealers receive preferential access to specific products. This opacity creates space for conspiracy theories to flourish. When information doesn’t flow freely, collectors fill gaps with speculation.

Counterpoint: Why This Theory Might Not Be True

Several strong counterarguments challenge the theory that breakers enjoy unfair advantages, and these explanations account for most of the observed patterns without requiring fraud or manipulation.

Odds & Volume

The most fundamental explanation involves simple mathematics. Breakers open far more product than individual collectors, creating an overwhelming volume advantage that naturally concentrates rare pulls in their hands. A serious breaking business might open 20 cases of a product in a single week. At 12 boxes per case, that’s 240 boxes. An individual collector might buy one box. The breaker has 240 times as many opportunities to pull premium cards. When rare cards appear in 1 of every 200 boxes, the breaker expects to encounter that hit at least once while the individual collector has only a 0.5 percent chance. The breaker’s success reflects probability operating at scale, not preferential treatment.

Only Big Hits Make the Cut

Selection and publication bias amplify this volume effect dramatically. Breakers film their breaks specifically to market their services and attract customers. They naturally highlight exceptional results and promote impressive pulls through social media. A breaker who opens 20 cases and hits three superfractors will create content featuring all three, generating dozens of social media posts, reaction videos, and promotional materials. The same breaker won’t create equivalent content about the 237 boxes that contained only base cards and standard hits. Individual collectors observe a curated highlight reel and mistake it for representative performance.

Favoritism Doesn’t Drive Sales

The economic structure of breaking actually argues against manufacturer favoritism. Card companies generate revenue by selling sealed products to distributors, who sell to retailers and breakers. Once that transaction completes, the manufacturer has already captured their profit and lacks incentive to care who pulls what from which boxes. Providing breakers with hot cases doesn’t increase manufacturer revenue unless it somehow drives additional sealed product sales. The causal chain connecting “breaker pulls good card” to “manufacturer sells more cases” exists, but it’s weak and indirect. Manufacturers could more easily boost sales through direct marketing, product design improvements, or athlete signings than through elaborate schemes to feed premium cards to specific breakers.

Conspiracies Require Secrets

Moreover, the conspiracy theory requires remarkable coordination and secrecy across multiple parties. Card manufacturers would need to identify selected breakers for preferential treatment, determine which specific cases contain better hits, ensure those cases reach the right breakers, prevent non-favored dealers from randomly receiving hot cases, and maintain absolute secrecy among everyone involved in the process. Every person with knowledge of the scheme represents a potential whistleblower. Distributors, warehouse workers, competing breakers who don’t receive favorable treatment, and manufacturer employees all would need to stay silent. The operational complexity and risk of exposure makes such conspiracy unlikely to survive at scale.

Independent Testing

Independent testing provides additional evidence against systematic manipulation. Some collectors and hobby investigators have purchased products from both breakers and traditional retail channels, documenting their pulls to compare hit rates. These studies generally find that results cluster around expected probabilities with normal statistical variance. While breakers occasionally beat odds, they also experience dry spells where boxes perform below expectations. The data doesn’t reveal consistent patterns suggesting preferential treatment.

The Industry’s Trust and Transparency Challenge

Regardless of whether breakers actually receive advantages, the perception that they might fundamentally alters the hobby’s ecosystem. Trust serves as the foundation of any collectibles market – collectors pay premium prices because they believe the products are authentic, fairly distributed, and contain the hits manufacturers promise. When that trust erodes, the entire market faces existential risk.

The breaking boom has created a bifurcated hobby where two distinct customer experiences exist side by side. Breakers open thousands of boxes on livestream while individual collectors quietly open products at home. These parallel experiences rarely intersect in ways that allow direct comparison. A collector can watch dozens of breaks showing exceptional results while their personal boxes consistently disappoint, and they have no reliable method to determine whether they’re experiencing bad luck or systematic disadvantage. This uncertainty feeds resentment.

How Manufacturers Have Responded

Card manufacturers have responded to these concerns inconsistently. Some companies have increased transparency about hit rates and collation processes, publishing detailed odds for specific inserts and parallels. These disclosures help collectors understand what to expect and evaluate whether breakers’ results seem anomalous. Other manufacturers maintain opacity, providing only vague language about hits being “randomly inserted” without specifics about frequency. This lack of detail creates exactly the information void where conspiracy theories thrive.

The breaking industry itself bears responsibility for trust deficits. While many breakers operate ethically and transparently, the lack of universal standards creates opportunities for bad actors. No licensing requirements or regulatory oversight govern breaking businesses. Anyone with a camera and sealed products can launch a breaking operation. Some breakers have been accused of tampering with products, selectively editing videos to hide mistakes, or failing to ship cards promptly. These incidents, even if they represent a small minority of breakers, poison the well for the entire industry.

Technology as a Solution

Technology offers partial solutions to transparency challenges. Many breakers now use third-party random number generators to assign teams, displaying the results on screen during breaks. Some break platforms incorporate escrow services where customer payments are held until cards ship. Advanced breakers use multi-camera setups showing product from all angles to prove they’re not switching boxes or manipulating outcomes. These measures help, but they can’t eliminate all doubt because sophisticated fraud could still occur off-camera.

The hobby’s growing professionalization may ultimately improve trust over time. As breaking transitions from informal hobby shop activity to serious business operations, market forces reward reputation and punish fraud. Breakers who develop reputations for fairness attract loyal customers willing to pay premium prices, while breakers suspected of cheating lose business to competitors. This competitive dynamic incentivizes ethical behavior more effectively than regulatory oversight might.

Does It Matter? The Future of Baseball Card Breaking

Breaking will almost certainly remain a dominant force in the baseball card hobby for the foreseeable future. The business model solves too many real problems for collectors – accessibility, affordability, and convenience – to disappear because of unfounded conspiracy theories. However, the industry will need to address trust concerns more directly if it wants to sustain long-term growth.

Regulation

One likely development involves increased standardization and self-regulation within the breaking community. Industry associations might establish best practices, certification programs, or ethical guidelines that legitimate breakers voluntarily adopt. These standards could include requirements for transparent sourcing, documented randomization procedures, and guaranteed shipping timelines. Breakers who achieve certification could display badges on their streams, signaling to customers that they meet professional standards. This approach borrows from other industries where voluntary certification creates market differentiation without requiring government regulation.

Technology will continue improving transparency and reducing opportunities for manipulation. Blockchain-based authentication might eventually allow collectors to verify the entire chain of custody for sealed products, from manufacturer to breaker to end customer. Advanced tamper-evident packaging could make it impossible to open and reseal products without leaving obvious evidence. Live streaming from multiple authenticated camera angles could provide near-absolute proof that breaks proceed fairly. As these technologies become cheaper and easier to implement, they’ll gradually become standard practice.

Sales Models

Card manufacturers might also embrace more direct-to-consumer models that reduce breakers’ influence. Some companies have experimented with official manufacturer-run breaks or online platforms where collectors can purchase randomized teams directly. These approaches eliminate the middleman and the associated trust concerns. If manufacturers stream their own breaks showing typical results, it becomes harder to argue that independent breakers receive preferential treatment.

Conclusion

The conspiracy theory itself, whether true or false, serves a function within the hobby ecosystem. It gives voice to collectors’ legitimate frustrations about accessibility and fairness. Many collectors feel priced out of high-end products and resent watching breakers casually open cases they could never afford. The theory that breakers are cheating provides a more satisfying explanation for this disparity than the uncomfortable truth that the hobby has become stratified by wealth. Addressing the conspiracy might require addressing the underlying economic anxieties it represents.

Ultimately, the question “do breakers get the best cards” probably matters less than ensuring that all participants in the hobby have access to fair, transparent, and enjoyable experiences. Whether breakers actually receive advantages or simply benefit from volume and selection bias, the hobby needs mechanisms to verify fairness and rebuild trust. Collectors should be able to participate in breaks or purchase retail products with confidence that they’re getting what they pay for. Breakers should be able to operate without constant suspicion undermining their business model. Manufacturers should be able to market products honestly without collectors assuming the demonstrations are rigged.

The baseball card hobby has survived numerous challenges over its long history – from the junk wax era’s overproduction crisis to the 1994 strike’s collector exodus to multiple fraud scandals involving grading companies and card doctors. The breaking conspiracy represents another test of the hobby’s resilience and ability to adapt. How the industry responds will determine whether breaking evolves into a legitimate, trusted pillar of the modern hobby or remains forever clouded by suspicion and doubt.