In today’s hobby landscape, where autographs, relics, and serial-numbered parallels often dominate attention, a surprising tradition is making its way back into the spotlight: the chase for complete sets. Collectors who once opened pack after pack in search of commons to slide into binders are returning to the patient, structured pursuit of filling every checklist number. Instead of being swept up in the chaos of short prints and infinite parallels, many hobbyists are rediscovering the satisfaction that comes from finishing what they started.

Baseball card sets have always represented more than just stacks of cardboard. They are snapshots of a season, time capsules that capture every star, role player, manager, and memorable moment. A complete set is more than an archive – it is a tangible record of an era in the sport. For collectors, the value lies not just in star rookies or iconic cards, but in the sense of order, progress, and completion that comes with sliding the final card into its slot.

The resurgence of set collecting is rooted in both nostalgia and psychology. Collectors who once built 1980s and 1990s binders of 792 cards are chasing that feeling again, while younger hobbyists are discovering why full checklists remain one of the most rewarding goals in the hobby. To understand why complete sets still matter, it helps to look at the history of baseball card sets, the psychology of completion, and the enduring appeal of a pastime that has outlasted countless market trends.

History of Baseball Card Sets

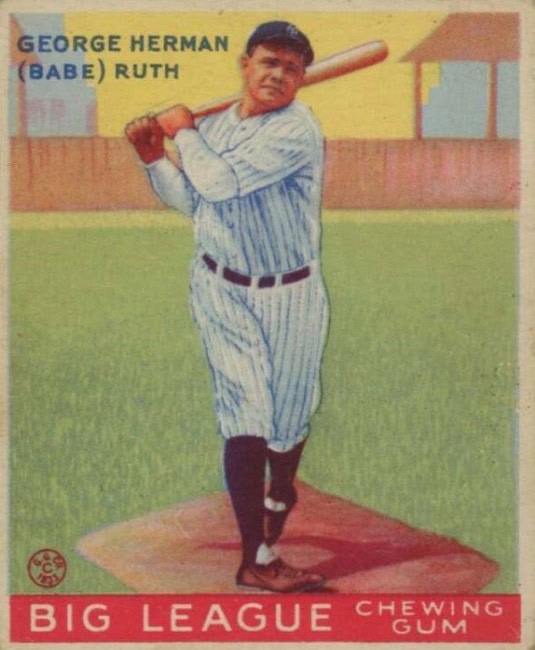

Baseball card collecting began in the late 19th century with tobacco issues like the Old Judge series and the legendary T206 set. At first, cards served as advertising premiums, slipped into cigarette packs to stiffen them and give buyers a reason to remain loyal to a brand. Over time, gum companies like Goudey and Bowman entered the market, producing colorful and more kid-friendly issues in the 1930s and 1940s.

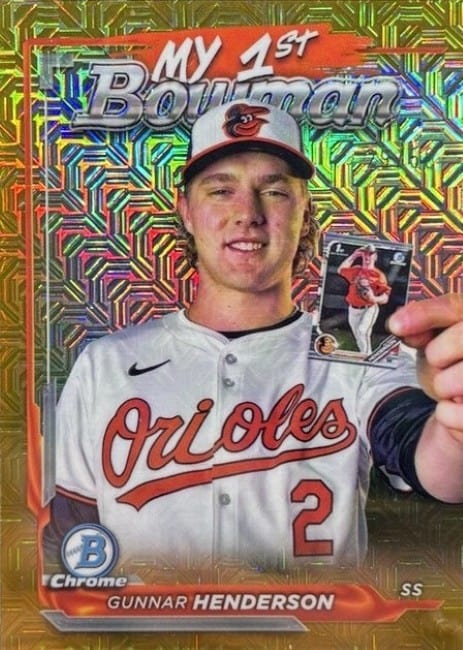

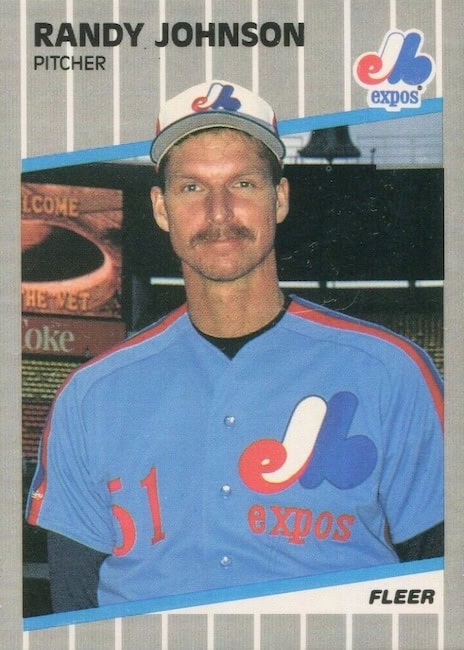

By the 1950s, Topps emerged as the dominant producer of baseball cards. Their flagship sets grew steadily in size as both the sport and the hobby expanded. What began with manageable sets of around 200 to 300 cards evolved into the massive checklists of the 1970s and 1980s, with Topps’ 792-card sets becoming the standard by the late 1980s.

These expansive sets provided coverage of nearly every player on a team, including role players, rookies, managers, and team leaders. They also gave fans a structured way to engage with the sport, not just chasing stars but immersing themselves in the full depth of Major League Baseball.

How Sets Are Numbered

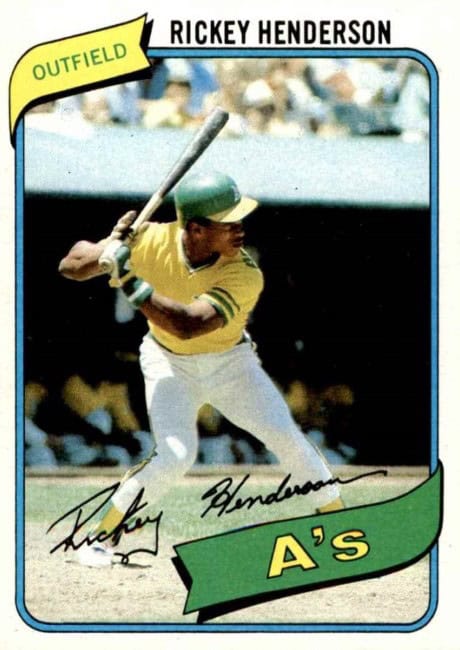

Collectors often underestimate how much thought goes into set numbering. Card companies rarely assign numbers at random. Stars are usually given milestone numbers like 100, 200, or 300. For example, Mickey Mantle often appeared on round numbers in Topps sets. In the 1980s, Cal Ripken Jr., Rickey Henderson, and Tony Gwynn could often be found on “hero” numbers. Today, Aaron Judge is often given his jersey number, #99. The first card in a set, like the 1951 Bowman Whitey Ford, also gets pride of place.

Numbering also reflects team sequences. Many sets grouped teammates together, so a collector flipping through could see an entire franchise represented within a narrow range. Special subsets, like league leaders, all-stars, and award winners, were usually clumped in sections rather than spread out randomly.

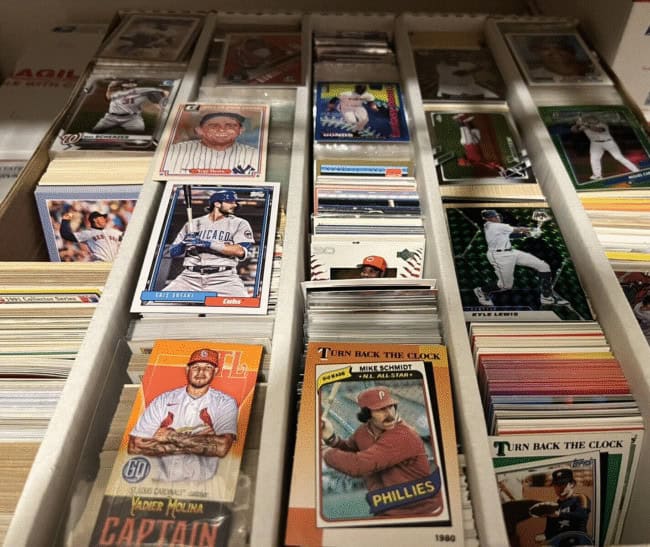

For builders, numbering creates a road map. It structures the chase and provides benchmarks. Completing each block of numbers gives a tangible sense of advancement. Unlike modern parallels, which are fragmented and often infinite, the numbering of a base set offers clarity and finality.

The Psychology of the Completionist

At the heart of set collecting lies a psychological drive rooted in completionism. Many collectors feel an inherent satisfaction from bringing order to chaos. Filling the last empty slot in a binder page provides a hit of accomplishment that cannot be replicated by opening a random pack of high-end cards.

Completionism has ties to basic cognitive processes. The Zeigarnik effect, which suggests that people remember uncompleted tasks more vividly than completed ones, helps explain why collectors fixate on missing cards. An incomplete set lingers in the mind, creating tension. Finishing the set resolves that tension.

Collectors also experience what psychologists call the endowment effect. Even before a set is finished, the incomplete binder or box already feels like “theirs.” Every card obtained adds to that sense of ownership. This differs from chasing single high-value cards, where the focus is transactional rather than immersive.

Value of Base Cards vs. Inserts

The modern card market often downplays base cards. Inserts, autographs, and relics dominate headlines, box breaks, and secondary markets. Yet base cards remain the foundation of the hobby. They are accessible, affordable, and plentiful.

Inserts, autos, and relics offer scarcity and excitement, but they lack the holistic narrative that base sets provide. A set builder can look at a completed checklist and see a snapshot of an entire season. Base cards democratize collecting, making it possible for fans without deep pockets to participate meaningfully.

The perceived lower value of base cards can actually benefit set builders. While others chase serial-numbered patches, the set collector quietly completes binders for a fraction of the cost. Over time, the cultural and historical value of a complete set often exceeds the market value of scattered relics or parallels.

Collecting Vintage Sets

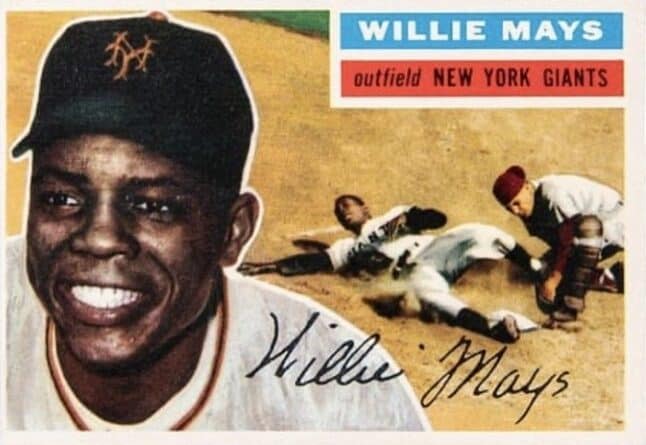

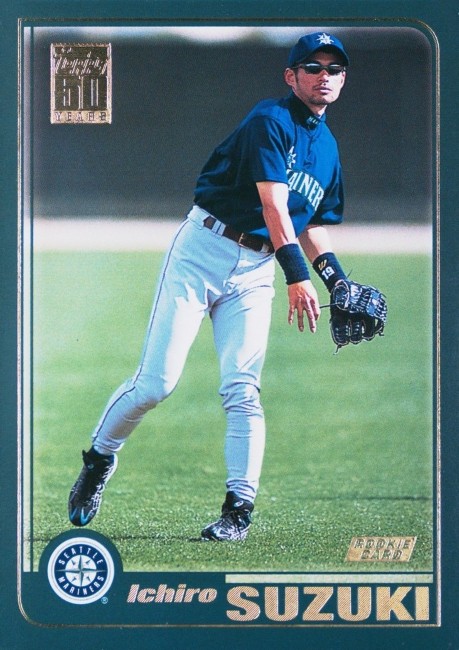

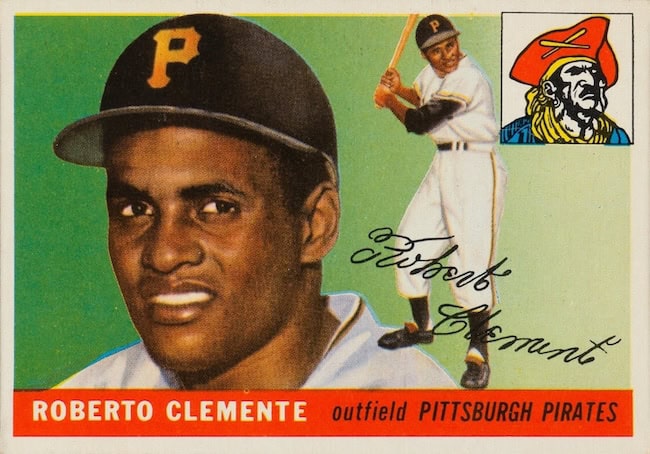

Building a vintage set offers both a historical and a personal connection to baseball’s past. Completing a 1956 Topps set, for example, gives a collector every key player from that golden era, including Mickey Mantle, Hank Aaron, and Willie Mays.

Vintage set building is not only about stars. It’s about context. Every bench player, every manager card, and every team card paints a full picture of the league. Many collectors describe a vintage set as a time capsule. Looking through a 1965 Topps binder is like flipping through the history of baseball itself.

Scarcity also plays a role. Vintage cards are harder to find in high grade due to decades of wear, poor storage, and the sheer passage of time. For some collectors, the hunt for well-preserved commons is as thrilling as finding a star card. The final product, a binder filled with sharp, colorful cards from a bygone era, carries immense personal satisfaction.

Famously Unattainable Sets

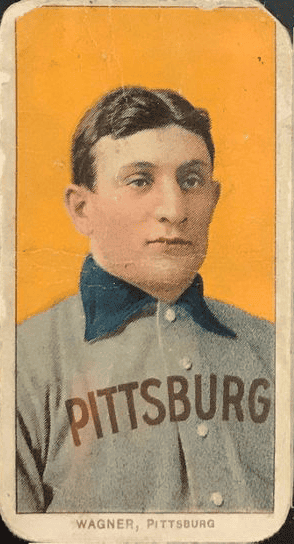

Not every set can be realistically completed. The most famous example is the T206 set, produced between 1909 and 1911. The full checklist features over 500 cards, with variations, multiple backs, and the iconic T206 Honus Wagner card. A complete T206 set is almost impossible due to the extreme rarity of Wagner, Eddie Plank, and a few other short prints. On the theoretical auction block, it would fetch countless millions.

The 1933 Goudey set is another famous example. Hall of Famer Napoleon Lajoie’s 1933 Goudey card was short-printed and part of a mail-in offer instead of being distributed with the rest of the set. Therefore, this is a difficult card to find, and completing the set – already rife with expensive cards – take quite an effort.

Another famously difficult sets include the 1952 Topps high numbers, including the #311 Mickey Mantle. Many of these cards were allegedly dumped into the ocean by the truckload after poor sales. Collectors chasing that set face steep prices for cards from the high series.

Unattainability does not always discourage collectors. In many cases, it enhances the chase. Even knowing they may never own a Wagner, collectors still piece together as much of the T206 set as possible. The journey, rather than the endpoint, becomes the source of enjoyment.

Why Set Collecting Is Resurging

Despite the dominance of high-end products, set collecting is making a comeback. There are several reasons for this trend:

- Affordability: Completing a set of base cards is far cheaper than chasing rare parallels.

- Structure: Sets provide a defined goal, which appeals to the human desire for order and accomplishment.

- Nostalgia: Many collectors grew up building sets in the 1980s and 1990s and are returning to the hobby with the same mindset.

- Community: Trading and networking remain part of the culture of set building. Swapping commons at shows or online forums creates bonds among collectors.

This resurgence is not about rejecting modern products. Many collectors still enjoy the thrill of pulling autographs or parallels. But the heart of their collection remains rooted in the structure and completeness of a set.

The Role of Technology in Modern Set Building

Technology has transformed the way collectors chase sets. Online marketplaces allow collectors to target specific needs instantly rather than relying on endless packs. Database tools and inventory apps make it easier to track progress. Online forums and social media groups create communities where traders can fill each other’s missing slots.

Yet technology has not replaced the satisfaction of physical completion. Even collectors who purchase singles online still experience the thrill of sliding a missing card into a binder. Digital tools assist, but the ritual remains tactile and personal.

Set Collecting as a Social Practice

Set collecting often operates as more than a solitary pursuit. It creates shared language and structure among hobbyists. At card shows, tables of commons draw steady attention from set builders combing through boxes. In online communities, collectors post “want lists” and trade for the sake of mutual progress.

Psychologists might describe this as a form of cooperative goal-seeking. The set collector’s objective aligns with others who hold duplicates or extras. The result is a web of reciprocal exchange that strengthens hobby ties.

Even within families, set building becomes intergenerational. Parents who built 1980s Topps sets often introduce their children to the process with modern equivalents. The ritual of building a set fosters patience, discipline, and persistence in a way few other collecting goals can.

Conclusion

Set collecting endures because it balances structure and challenge. It appeals to cognitive psychology, taps into nostalgia, and provides a sense of accomplishment unmatched by chasing scattered hits. In an era defined by scarcity-driven inserts, the completeness of a full set feels timeless.

The resurgence of set collecting shows that the hobby is not just about value or rarity. It is also about meaning, order, and the satisfaction of completion. Whether a collector builds a 1956 Topps masterpiece, assembles commons from the 1987 Topps wood grain design, or dares to chase the impossible T206, the journey unites hobbyists across generations.

For some, the thrill of a one-of-one patch card will always hold sway. But for those who still slide cards into nine-pocket pages, the chase for 792 remains a hobby worth embracing.