Baseball card collecting has always balanced two competing impulses: the joy of personal attachment and the lure of financial value. In recent decades, grading companies have tipped that balance heavily toward investment. A single digit on a label can determine whether a card sells for a few dollars or several thousand. Collectors who follow the graded path treat cards as assets, moving them through the marketplace like commodities. Yet, another culture thrives beneath the headlines – the personal collection.

Personal collection (PC)-focused collectors pursue raw cards, full sets, and items that resonate with memory or identity. They are not motivated by resale value. Instead, they view cards as artifacts of baseball history, as objects to curate, and as extensions of self.

This counterculture has deep roots in the hobby. To understand its rise, one must return to earlier eras of collecting, before money dominated the narrative, and follow its evolution through decades of social and cultural change.

Collectors Before Money Entered the Hobby

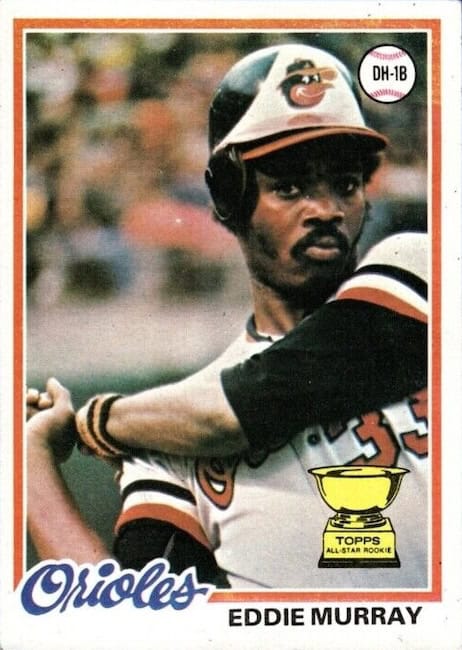

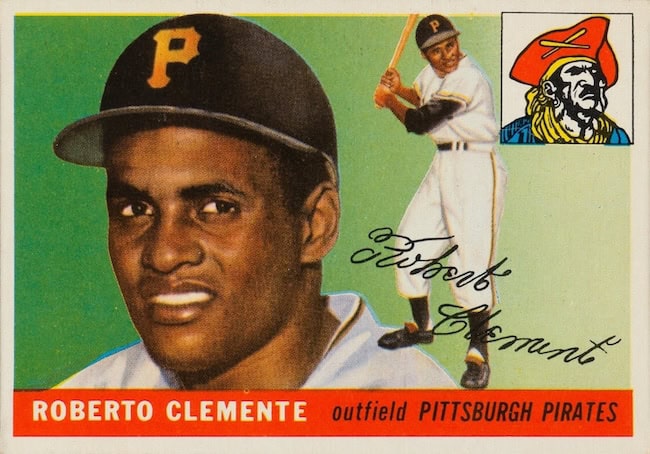

In the 1950s, baseball cards were primarily for children. Packs cost pennies, and the included gum was often valued as much as the cards themselves. Collecting was driven by curiosity, competition, and the simple thrill of finding one’s favorite player.

Kids flipped cards against walls, traded them on playgrounds, and tucked them into lunchboxes. Condition mattered little, because the purpose was not preservation but enjoyment. A card folded into the spokes of a bicycle wheel carried as much personal meaning as a mint copy tucked away today.

For many of these children, baseball cards became woven into the fabric of daily life. They symbolized fandom and community, but also embodied personal identity. To have a Mickey Mantle card in a stack meant you could proudly show allegiance to greatness. Owning a complete run of your hometown team was a badge of dedication.

The key psychological distinction in this pre-money era was that cards were ends in themselves. They were valued for what they represented, not for what they might be worth in the future. Adults who saved their childhood boxes did so because of sentiment, not foresight. This mindset forms the bedrock of today’s PC movement.

How Collectors Stored Their Cards

Storage practices in these eras reflected the priorities of the time. Cards went into shoeboxes, cigar boxes, or rubber-banded stacks. Some children glued them into scrapbooks, permanently affixing images of their heroes onto pages of construction paper.

The act of gluing a Willie Mays card into a book may horrify modern investors, but for the child doing it, the motivation was clear: display, not profit. Having the image preserved in a scrapbook made it more permanent, not less.

These casual storage practices also highlight an important psychological truth. The cards were tools for interaction, not fragile artifacts. They were handled, traded, and displayed frequently. The very scarcity of high-grade vintage cards today stems from this carefree approach. But what modern investors see as flaws, PC collectors often interpret as stories.

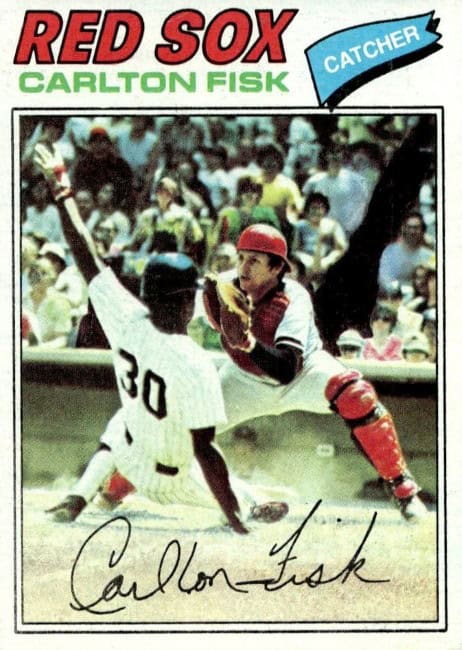

The Shoebox Era of the 1970s

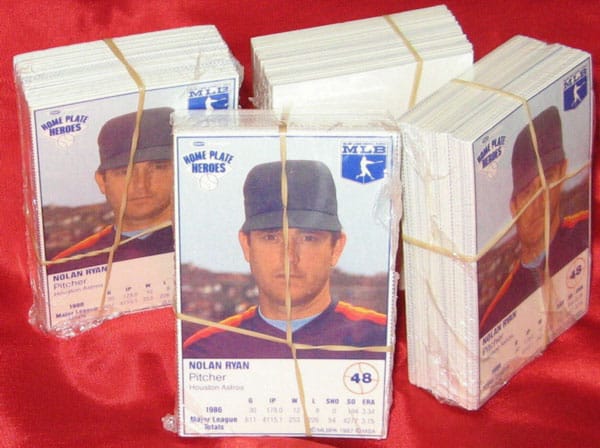

By the 1970s, a generation of collectors who grew up in the 1950s had begun to revisit their childhood hobby. Shows and shops began to emerge, and Topps expanded production to meet demand. The “shoebox era” became a defining symbol.

Collectors still stored cards in simple ways, often using shoeboxes to house growing collections. The shoebox was not just storage – it was a treasure chest. Flipping through stacks of cards represented both order and surprise. A collector could find a favorite player, stumble upon an oddball card, or admire the design of a particular year.

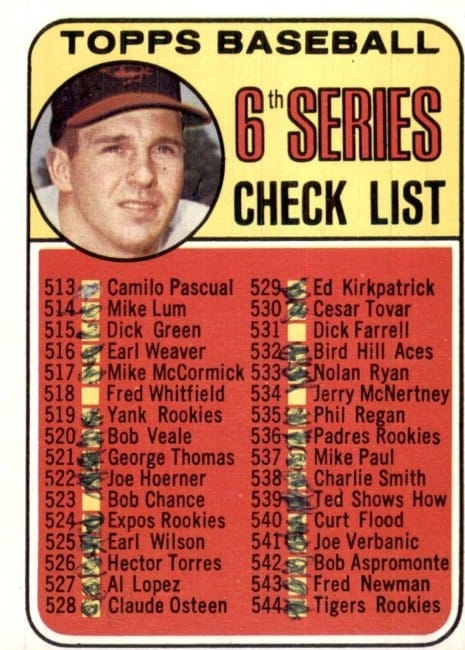

This era also saw the birth of organized set collecting. Checklists, published in hobby newsletters, gave structure to collecting efforts, and manufacturers began to include checklists in their official releases. Completing an entire set became a goal for adults as much as for children. The practice of chasing completeness represented a shift in psychology: collectors wanted order, harmony, and narrative from their collections.

The shoebox culture of the 1970s remains central to the PC ethos. Accessibility, tangibility, and completion mattered more than pristine condition or financial appreciation.

The Rise of Grading in the 1990s

The 1990s brought seismic changes. PSA, founded in 1991, introduced third-party grading as a standard. Suddenly, numerical assessments defined value. A PSA 9 or 10 rookie card could sell for multiples of its raw counterpart. The marketplace became obsessed with sharp corners, centering, and population scarcity.

For many, grading created legitimacy and liquidity. Investors treated cards like stocks, chasing the next rookie prospect or grading their vintage finds for maximum resale value. This speculative culture culminated in the late 1990s boom and the later rise of auction houses specializing in high-grade cards.

But the rise of grading also sparked resistance. Many collectors who had been active in the shoebox era recoiled at the intrusion of financial motives. They rejected the idea that enjoyment required a slab. Instead, they doubled down on the PC approach, emphasizing sets, players, and themes that meant something personally.

The psychological split widened. Grading culture appealed to investors who valued scarcity and precision, while PC culture appealed to those who valued memory, aesthetics, and connection.

Complete Set Collecting

Across all eras, set collecting has provided structure and meaning. Building a complete set transforms an endless sea of cards into a finished narrative. It creates closure. Those cards are numbered for a reason!

Psychologists describe this as the appeal of “completionism.” Humans find satisfaction in completing tasks and closing loops. In baseball card collecting, this translates into the thrill of adding the final missing number to a checklist.

For PC collectors, the set holds meaning beyond individual stars. A 1969 Topps set tells the story of an entire season. Commons, often overlooked in the graded market, become vital pieces of the whole. Each card contributes equally to the sense of completion.

Modern PC collectors continue this tradition, building flagship Topps runs, Heritage sets, or unique thematic collections. The pleasure comes from the act of building, not from resale.

Collecting What They Want

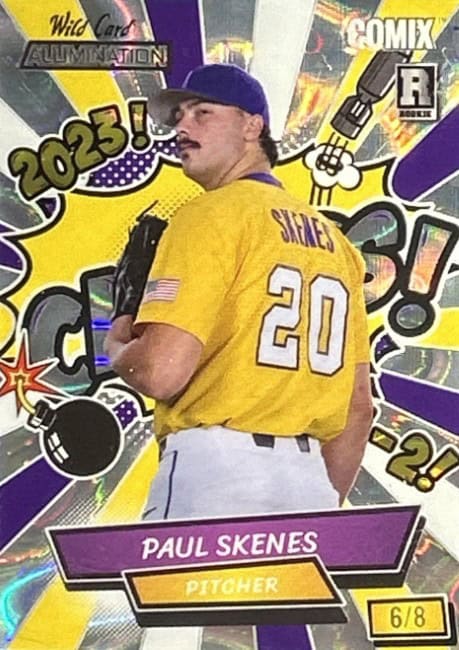

Another defining trait of PC collectors is freedom from market dictates. They collect what speaks to them, whether or not it carries financial value.

This may mean building team-specific collections, pursuing oddball issues like Hostess panels or Kellogg’s 3-D cards, or pursuing a rainbow of parallels. Some PCs focus entirely on a single player’s career, regardless of condition or rarity.

The psychological foundation here is intrinsic motivation. Unlike investors motivated by extrinsic rewards (profit), PC collectors are driven by internal satisfaction. They follow personal taste rather than external pressure. This autonomy strengthens commitment and deepens enjoyment.

The Psychology of the Personal Collection

At the core of the PC mindset lies a distinct psychological orientation. Several themes illustrate why collectors choose personal meaning over profit:

- Identity expression – A PC becomes an extension of self. It reflects values, allegiances, and tastes.

- Nostalgia and memory – Cards act as time machines, linking collectors to childhood and to the history of the game.

- Control and order – Building sets or themed collections provides structure and closure.

- Aesthetic engagement – Raw cards allow direct appreciation of design, photography, and tactile qualities.

- Resistance to commodification – PCs represent a conscious refusal to let market trends define enjoyment.

Social Dimension of PCs

PC collecting also fosters community. Parents often introduce children to the hobby through PCs, encouraging exploration without the fear of damaging expensive slabs. Card shows and online forums thrive on raw card trades, where affordability creates inclusivity.

The PC culture promotes relationships. Collectors share stories about why certain players matter to them, trade extras to help others complete sets, and build connections based on shared enthusiasm rather than financial competition.

In this way, PCs restore the social function of collecting. The hobby becomes about people as much as cards.

High Value and Graded Cards in PCs

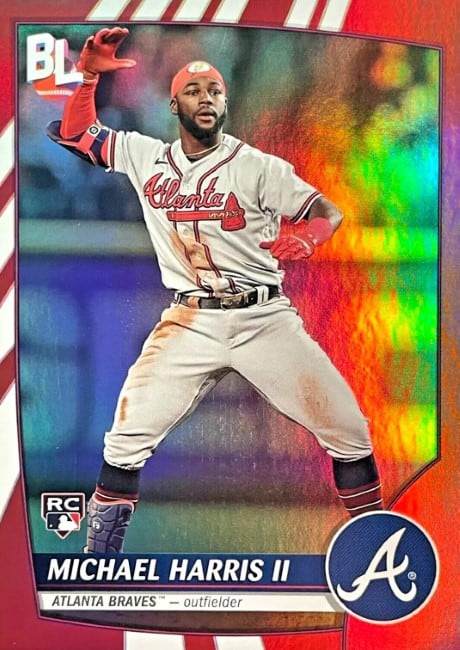

Not every personal collection avoids high-value or graded cards. For some collectors, the point is not rejecting the grading industry or the secondary market but rather choosing what resonates most with them. A player collector, for example, might chase every known card of a favorite star, which naturally includes premium parallels and professionally graded examples. The card’s value is secondary to its place within a carefully built theme that reflects the collector’s own passion.

Graded cards can also serve as a way to ensure that centerpiece items stay preserved over the long term. Someone who values a rookie card of a Hall of Famer may prefer a slabbed copy because it provides both protection and peace of mind, even if they have no intention of selling. In these cases, the presence of a graded card in a personal collection doesn’t contradict the spirit of a PC. Instead, it shows that personal collections are flexible spaces, shaped by individual taste and comfort rather than any outside definition of what they should be.

What ties these collections together is the intention behind them. Whether a box is filled with obscure commons, colorful parallels, or carefully graded treasures, the driving force remains the same: the collector builds it because they enjoy it, not because they expect a return on investment. That personal choice, whether it includes expensive slabs or overlooked oddballs, defines the enduring appeal of a PC.

The Future of Personal Collections

The future of PC collecting looks bright. Younger collectors, priced out of high-grade slabs, often enter through affordable raw cards. Many discover that the joy of building a personal collection outweighs speculative gain.

Technology provides new ways to share PCs. Collectors catalog and display their work online, trading images and stories while maintaining the tactile joy of physical cards. The sensory experience – flipping through stacks, completing sets, and arranging themes – remains irreplaceable.

PCs also sustain the hobby by broadening access. They keep baseball card collecting inclusive, affordable, and rooted in meaning.

Conclusion

The rise of the personal collection marks a conscious rejection of commodification. By focusing on sets, themes, and players that matter personally, PC collectors preserve the deeper essence of baseball card collecting.

Their approach reminds us that cards are more than assets. They are cultural objects tied to memory, identity, and joy. As grading culture continues to dominate the headlines, the growth of personal collections ensures that baseball card collecting remains a practice grounded in human meaning rather than financial speculation.