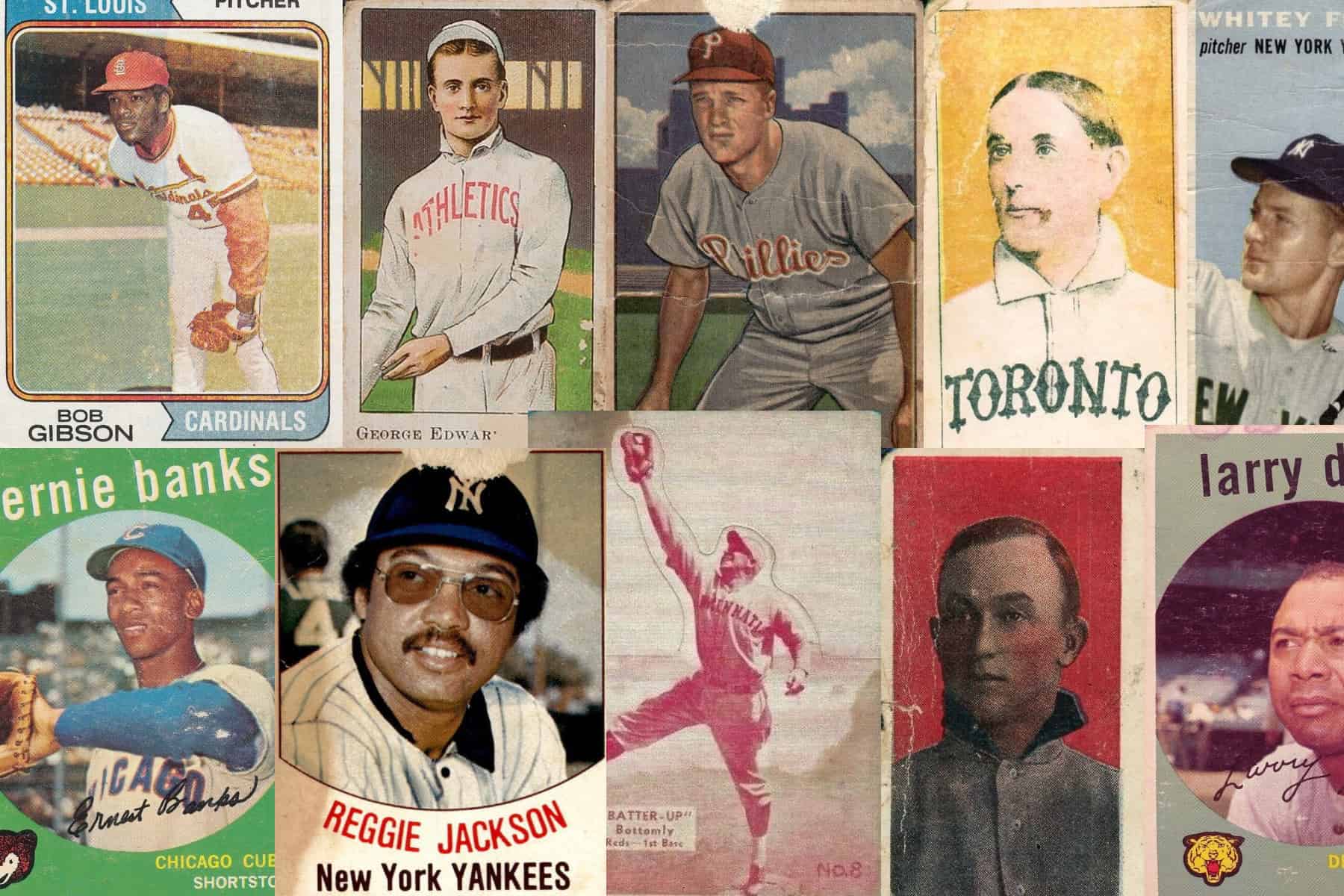

In a hobby where condition is one of the most important factors in determining value, it’s no surprise that baseball cards have long been targets for alteration. Every scuff, crease, stain, or soft corner can affect a card’s grade and marketability. Because collectors place such high importance on appearance and preservation, some individuals have attempted to enhance cards through physical modification. These card alteration efforts vary in intensity and intent, but all raise important questions about authenticity, ethics, and long-term value.

This article explores the major types of card alteration, detailing how each method is performed and why some individuals resort to them. It also examines the impact alterations have on a card’s value, how third-party grading companies detect and respond to altered cards, and why authentication processes continue to evolve. Finally, the article looks at some of the most well-known alteration controversies in the hobby’s history and considers how technology is changing the landscape for collectors, sellers, and graders alike.

Common Types of Alteration

Alterations typically aim to improve a card’s appearance or grade. Some are cosmetic, while others involve structural changes. The most common include:

- Trimming

- Bleaching

- Coloring

- Surface repair

- Rebacking

- Gloss enhancement

Each of these has a unique set of techniques and consequences, both for the card and the hobby.

Trimming

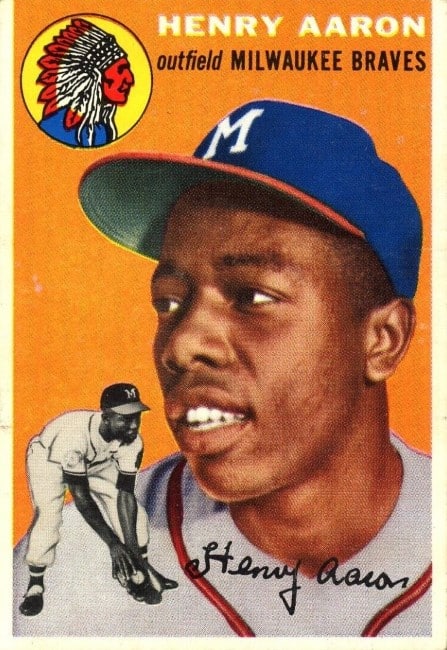

Trimming involves cutting down a card’s edges to remove wear, improve centering, or restore uniformity. Collectors often encounter trimmed cards when dealing with high-dollar vintage examples.

The process usually begins with precise measurements. A hobbyist might use calipers to check a card’s dimensions down to the hundredth of a millimeter. Then, a blade or paper cutter is used to remove a very thin strip from one or more edges.

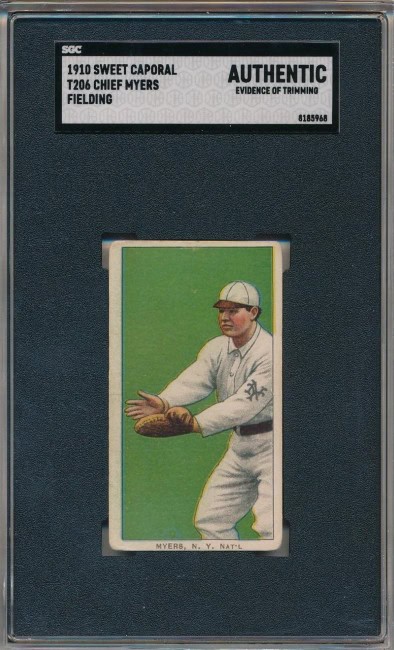

Professionals make this look seamless. A well-trimmed card may appear clean and sharp, with edges that mimic factory quality. However, trimming alters the card’s original dimensions. It eliminates natural edge fibers and creates corner angles that differ from authentic factory cuts. These signs are hard to catch with the naked eye but become obvious under magnification.

Grading companies regularly reject trimmed cards. If detected, the card will be marked as “Altered” or “Minimum Size Not Met.” Once labeled, the card’s resale value drops significantly. Collectors tend to avoid trimmed cards even when the alteration is disclosed.

Bleaching

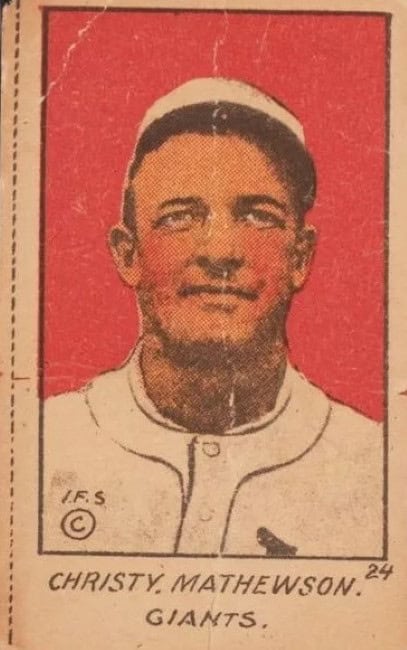

Bleaching is used to lighten cards that have yellowed or become stained. The goal is to make the card look cleaner and closer to its original condition. This technique is most common with tobacco-era cards or cards exposed to moisture.

Bleaching solutions range from household chemicals to commercial paper brighteners. In most cases, the card is either spot-treated or fully soaked. The chemical reaction removes visible stains, but it also breaks down the paper’s cellulose structure. Over time, this can make the card more brittle or give it an unnatural tone.

A bleached card often loses its depth of color. It might appear flat or overly white, especially when compared to other cards from the same set. Graders check for this using UV light, loupes, and color reference charts.

Bleached cards usually receive the “Altered” label. Even if they retain structural integrity, their artificial appearance and chemical modification push them outside the bounds of authenticity.

Coloring

Coloring is the application of pigment to hide flaws or restore surface uniformity. While it can improve a card’s visual appeal, it significantly alters the original print.

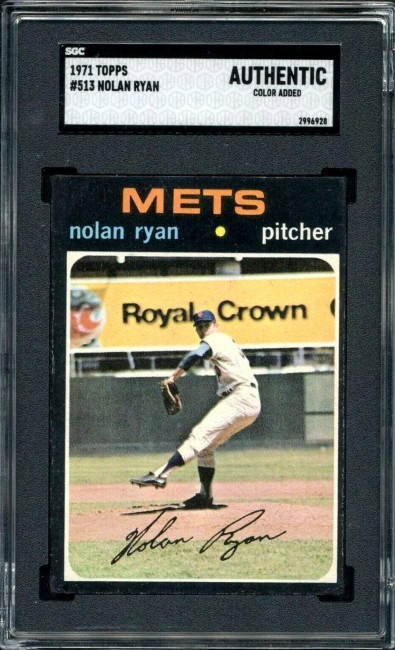

Collectors have used everything from fine-tipped pens to acrylic paint. Edges and corners are common targets, especially when whitening or paper loss occurs. In some cases, ink is used to fill in missing areas or cover light creases. Sets like the 1971 Topps and 1986 Donruss, which both have black borders, frequently chip, and may be colored in.

When viewed under blacklight, the added pigment fluoresces differently than factory ink. Coloring also tends to pool unevenly, and it may bleed into the surrounding fibers. Graders are trained to spot these inconsistencies.

Even when the coloring is well done, the card is considered altered. Value decreases sharply, and the card loses its eligibility for numeric grading by most third-party services.

Surface Repair

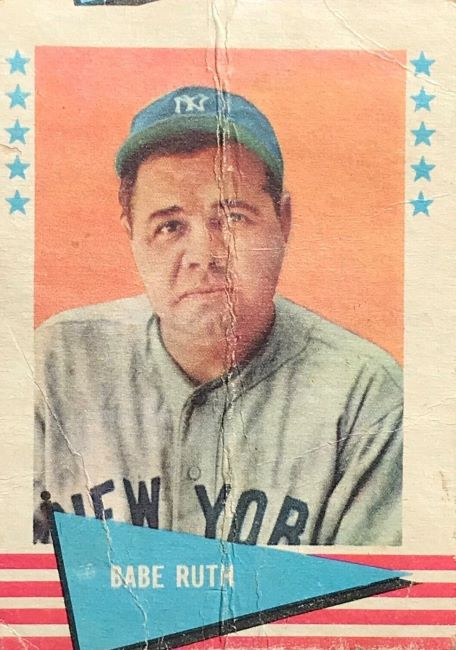

Surface repair involves manipulating the card’s physical structure to eliminate visible damage. Common issues addressed this way include wrinkles, dents, creases, and tears.

One technique is card pressing. The card is placed between heavy materials and compressed to flatten out imperfections. Some use heat in combination with pressure, although that adds risk of ink melting or surface gloss distortion.

For deeper damage, such as gouges or missing layers, some restorers apply fillers. This might involve gluing layers of paper to rebuild corners or using a clear adhesive to fill scratches. Others go as far as sanding down a surface to remove abrasions.

These methods are difficult to detect without careful inspection, but they are considered alterations nonetheless. Pressing often leaves subtle signs, such as surface tension lines or changes in texture. Once discovered, repaired cards are labeled as altered and generally lose value compared to their unaltered counterparts.

Rebacking

Rebacking is one of the most extreme forms of alteration. It involves attaching the front of one card to the back of another. This is usually done when the front is relatively clean, but the original back is badly damaged or missing (often by gum stains or glue).

Alignment must be precise. The altered card is then trimmed or pressed to match standard dimensions. When done skillfully, the result can look convincing. However, inconsistencies in gloss, layering, or card thickness usually reveal the deception.

Grading companies automatically reject rebacked cards. The process destroys the original integrity of the card, making it ungradable and heavily reducing its value. Most collectors view rebacking as an act of forgery rather than repair.

Gloss Enhancement

Gloss enhancers are used to simulate the shine of factory-fresh cards. This method is common with cards from the 1980s and 1990s, where dulling or scuffing is frequent.

Some restorers use furniture polish, automotive wax, or commercial sprays. These can create a smooth, reflective surface that resembles the original gloss. Others use clear sealants to reduce the appearance of scratches.

The result may look appealing, but it changes the surface feel and introduces chemicals not present during original production. Grading companies test for surface irregularities and often find traces of residue. Enhanced cards are almost always flagged as altered, and their market value declines accordingly.

Why People Alter Cards

The motivations for card alteration vary. Some do it for money, others for personal satisfaction. A few see it as preservation.

Profit remains the primary driver. High-grade cards command a premium. The jump from PSA 6 to PSA 8 can mean a value increase of 5- or 6-figures for certain cards. Some speculators alter cards hoping they will pass through grading undetected. If they don’t, they may try to pass them through at a different time, or with a different grading company.

Aesthetic preference is another factor. Collectors sometimes alter cards in their personal collection to make them more visually pleasing, even if they never intend to sell.

Finally, there’s a philosophical argument from those who treat card alteration like art conservation. They believe that with proper documentation, restoration should be acceptable, just as it can be for fine art. This view remains controversial. Most grading companies and serious collectors see any physical alteration as unacceptable, regardless of intent.

How Grading Companies Respond

Third-party grading companies like PSA, SGC, and Beckett have developed advanced tools to detect altered cards. These tools include:

- Microscopes and loupes to check edge consistency

- UV lights to detect foreign inks and chemicals

- Calipers to measure card thickness and size

- Image comparison systems to flag re-submissions

If a card is found to be altered, it may be rejected, slabbed as “Authentic – Altered,” or marked with a comment like “Evidence of Trimming.” This designation significantly reduces market value and often makes resale difficult.

In some cases, grading companies have revoked prior certifications after later discovering alterations. These revocations have occurred with high-profile cards, leading to calls for more stringent submission tracking and transparency.

Famous Alteration Cases

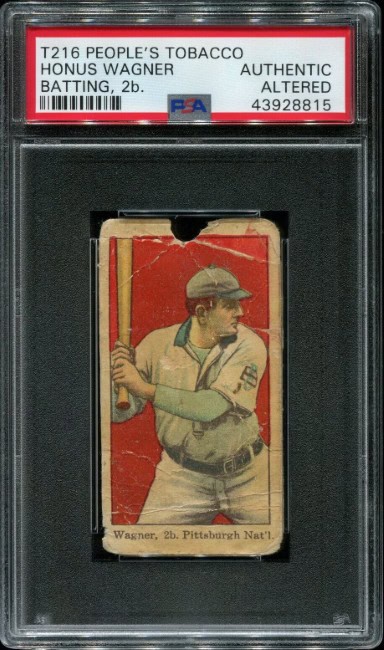

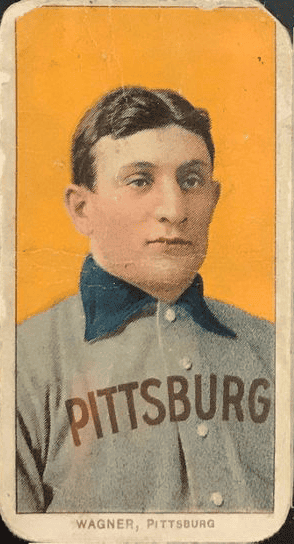

The Gretzky T206 Honus Wagner

No card is more famous – or controversial – than the T206 Honus Wagner once owned by Wayne Gretzky. For years, it was celebrated as the finest example of the hobby’s most iconic card. It appeared smaller than other Wagners and had unusually sharp corners. Rumors swirled about trimming.

In 2013, former auction house executive Bill Mastro admitted in court that he had trimmed the card. Despite this revelation, the card continued to increase in value. Many collectors now see its altered state as part of its unique story. Still, the case highlighted how difficult it can be to detect even severe alterations without insider knowledge.

The PWCC and Blowout Forum Scandal

Between 2017 and 2019, members of the Blowout Cards forum began tracking high-end cards that had been trimmed or altered, then resubmitted to grading companies for higher grades. Many of the cards were traced to PWCC auctions, although the company denied wrongdoing.

Dozens of before-and-after photos revealed trimming, pressing, and recoloring. Some cards had changed hands multiple times with progressively higher grades. The investigation prompted PSA and other graders to enhance their detection protocols and add a database of card images to catch resubmissions.

This scandal shook confidence in grading systems and encouraged collectors to look more critically at certified cards.

How Collectors Can Protect Themselves

Most collectors don’t have access to grading tools, but there are still ways to avoid altered cards:

- Compare suspect cards to high-resolution images of known authentic examples

- Use a loupe to check for edge consistency and ink irregularities

- Check the card’s size with a precise ruler or caliper

- Avoid cards with unusually sharp corners or inconsistent gloss

- Research the seller’s history and reputation

Buying from trusted dealers, especially those who offer return policies, also adds protection. If something looks too good to be true, it often is.

Alteration vs Restoration

The line between alteration and restoration isn’t always clear. A collector who gently flattens a card to remove a crease may believe they’re preserving it. But if the process changes the card’s original structure or materials, graders will likely call it altered.

This mirrors debates in the art and antiques world. Restoration, when disclosed, can be acceptable in some fields. But in card collecting, where originality is tightly linked to value, even minor modifications tend to be rejected.

Cards with known alterations may still have value, especially if rare. However, they occupy a different space in the hobby and are often harder to sell or insure.

The Role of Technology

Technology is transforming the way card alterations are detected, making it increasingly difficult for modified cards to slip through the cracks. Leading grading companies are investing heavily in artificial intelligence and machine learning systems that analyze minute details such as changes in card shape, ink consistency, print alignment, and surface texture. These systems compare submitted cards against vast archives of authentic examples to identify subtle differences that human eyes might miss.

In addition to AI, some companies are exploring blockchain technology to create permanent, tamper-proof digital fingerprints for high-end cards. By recording detailed information about a card’s condition, provenance, and history on an immutable ledger, blockchain can help verify authenticity and track any changes over time. This approach offers a new layer of security, building collector confidence and reducing the potential for fraud.

Together, these technological advances promise to make card alteration far less profitable and more transparent. As grading protocols improve and collectors gain access to better verification tools, the likelihood of successfully passing off altered cards diminishes. This ongoing evolution is crucial for protecting the hobby’s integrity and ensuring that collectors can invest with greater peace of mind.

Conclusion

Card alteration remains a serious concern in the hobby. From trimming and bleaching to full-on rebacking, each method compromises a card’s authenticity and changes its place in the collecting world.

Understanding these practices helps collectors make informed choices. Whether you’re buying raw cards or slabbed gems, knowing how alterations are done and detected is essential. The goal isn’t to fear every transaction, but to build a collection based on trust, transparency, and knowledge.

By staying informed and alert, collectors can protect the integrity of their investments and preserve the history that makes baseball cards more than just ink on cardboard.