Every collector knows the thrill of pulling a rare card from a pack or discovering an undervalued gem at a card show. But what actually makes one piece of cardboard worth $5 while another commands $500,000? The reasons behind baseball card values reach far beyond statistics, rookie years, or Hall of Fame credentials. Baseball card values emerge from a fascinating intersection of economic principles and human psychology, where scarcity drives desire and cognitive biases shape markets in ways collectors don’t always recognize.

The baseball card market operates as a perfect laboratory for observing fundamental economic forces at work. Unlike stocks or bonds, cards generate no dividends or interest. Baseball card values exists purely in what collectors will pay for them, making the market a direct reflection of supply, demand, and human psychology. Understanding these forces helps collectors make smarter decisions, whether they’re building a personal collection or viewing cards as alternative investments.

This article explores the economic and psychological mechanisms that determine baseball card values. We’ll examine how artificial scarcity shapes modern card production, why our brains trick us into overvaluing certain cards, and how market psychology creates both opportunities and pitfalls. By understanding these hidden forces, collectors gain insight into one of the most dynamic collectibles markets in existence.

The Economics of Manufactured Scarcity

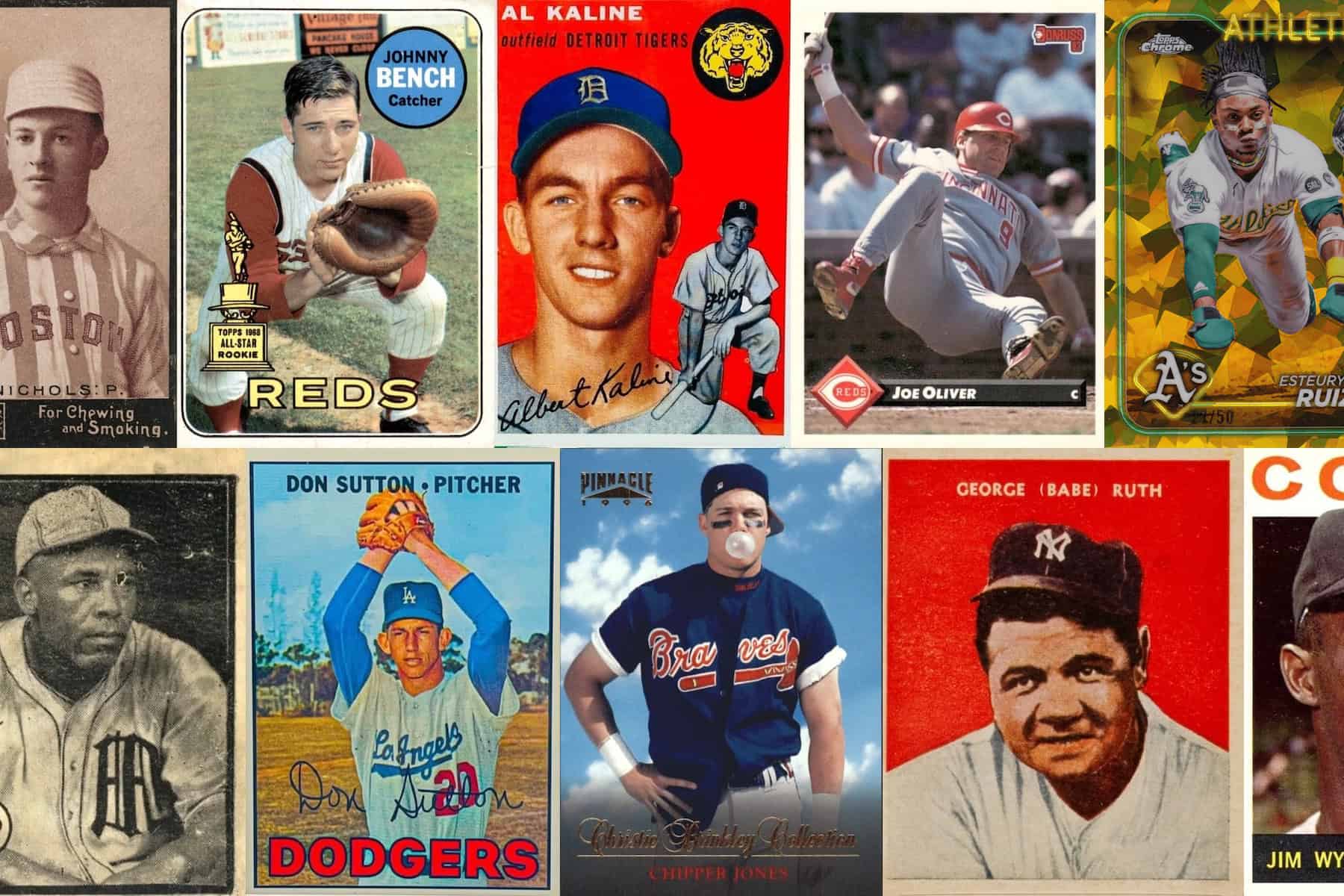

Card manufacturers learned a painful lesson during the overproduction era of the late 1980s and early 1990s. When companies flooded the market with billions of cards, baseball card values collapsed. A 1990 Donruss Frank Thomas rookie card that once sold for $20 now struggles to reach $2. The market correction taught the industry that scarcity drives value, and modern card production reflects this principle with surgical precision.

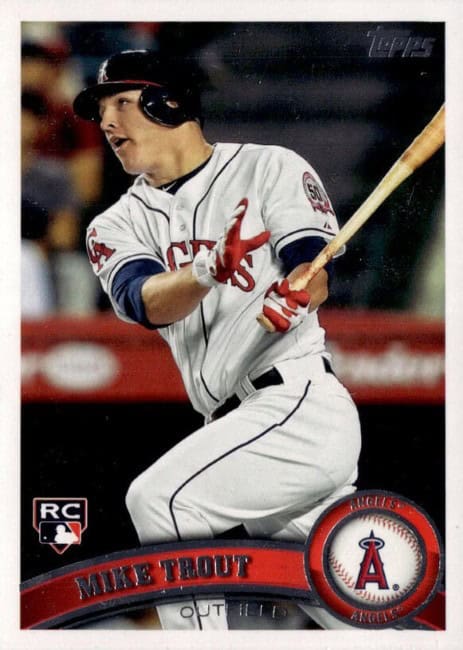

Today’s manufacturers create scarcity through numbered parallels, short-print variations, and limited-edition releases. When Topps produces a card numbered to 25 copies, they’ve engineered rarity into the product. This manufactured scarcity generates value where none would otherwise exist. Two cards featuring identical images and players can differ in value by thousands of dollars based solely on artificial production limits. The 2011 Topps Update Mike Trout base card sells for around $100, while the same card in the Cognac parallel (numbered to 25) fetches over $10,000.

The economics here follow the basic supply-demand curve that Adam Smith described centuries ago. By restricting supply while maintaining or increasing demand through marketing and product design, manufacturers create premium products that command premium prices. Collectors participate willingly in this system because scarcity generates excitement and gives chase cards aspirational value.

The Paradox of Vintage Baseball Card Values

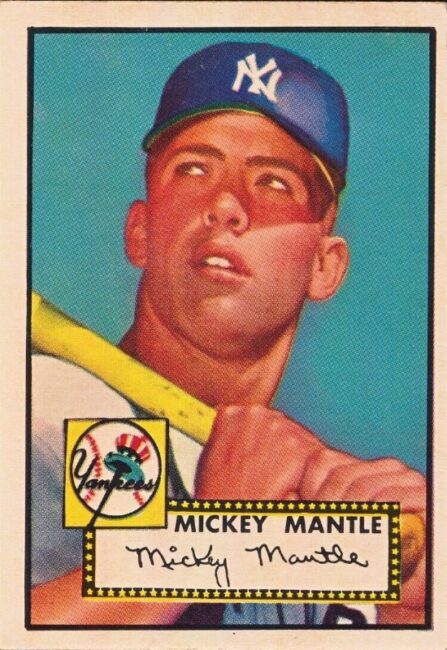

Vintage cards present an interesting economic puzzle. Production runs from the 1950s through 1970s often exceeded modern print runs of limited edition cards. The key lies not in original scarcity but in survival rates and condition rarity.

Environmental factors destroyed the vast majority of vintage cards. Kids stuck them in bicycle spokes, rubber-banded them together, and stored them in damp basements. This natural attrition created genuine scarcity over time. The population of high-grade vintage cards grows more slowly than demand, particularly as wealthy collectors enter the market seeking trophy cards. Economic theory predicts that when a fixed or slowly growing supply meets increasing demand, prices rise – sometimes dramatically.

The vintage market also benefits from historical significance and nostalgia. Cards from baseball’s golden age carry cultural weight that modern cards cannot replicate. This intangible value adds a premium that purely economic models struggle to capture. A 1954 Hank Aaron rookie represents not just a baseball player but an entire era of American history. Collectors pay for that connection as much as for the cardboard itself.

Loss Aversion & the Endowment Effect

Behavioral economics reveals why collectors often struggle to sell cards for rational prices. The endowment effect describes how people value items they own more highly than identical items they don’t own. Psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky demonstrated that people demand roughly twice as much to give up an object as they would pay to acquire it. This bias pervades the baseball card market.

Watch collectors discuss their holdings and you’ll witness the endowment effect in action. “I know it books for $200, but I wouldn’t sell it for less than $300” reflects not greed but a cognitive bias that makes owned cards feel more valuable. This psychological phenomenon can trap collectors in unprofitable positions, holding cards as they decline in value rather than accepting losses.

Loss aversion compounds this effect. Research shows that losses feel roughly twice as painful as equivalent gains feel pleasurable. A collector who bought a card for $1,000 and sees it drop to $700 experiences psychological pain that exceeds the pleasure they’d feel from a $300 gain. Rather than realize the loss, many collectors hold indefinitely, hoping for recovery. This behavior creates market inefficiencies where cards remain locked away rather than finding their proper market level.

Anchoring & Reference Prices

The human brain relies heavily on anchors – initial pieces of information that shape subsequent judgments. In the card market, anchoring affects both buyers and sellers in powerful ways. When a collector sees a 2018 Ronald Acuna rookie auto sell for $1,500, that number becomes an anchor for future valuations, even as market conditions change.

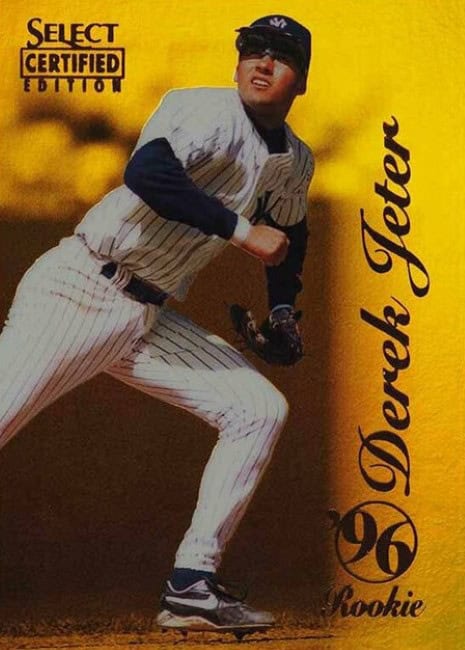

Price guides and recent sales data create anchoring effects throughout the hobby. A collector who remembers when Derek Jeter rookies sold for $300 may perceive current $150 prices as bargains, regardless of whether that valuation makes sense given supply and demand. Conversely, someone who entered the hobby during the 2020-2021 boom may view those same cards as overpriced based on their experience with higher anchors.

Savvy sellers exploit anchoring by listing cards at high asking prices, making subsequent offers seem more reasonable. A card listed at $500 makes a $350 counter-offer feel like a deal, even if market value sits closer to $300. Buyers can counter this bias by researching actual sold prices rather than asking prices, creating more accurate anchors based on real transactions.

The Psychology of Grading & Perception

Card grading represents a fascinating intersection of objective measurement and subjective value. PSA, BGS, and SGC provide standardized assessments of condition, but the market’s response to those grades reveals psychological forces at work. The difference between a PSA 9 and PSA 10 often comes down to centering within millimeters or corner sharpness under magnification, yet prices can differ by multiples of five or ten.

This outsized premium for perfection reflects the human attraction to superlatives and completeness. Collectors don’t just want nice cards – they want the best cards. The “finest known” designation carries psychological weight beyond its practical significance. This cognitive bias drives prices for gem mint examples to levels that pure condition differences can’t justify economically.

The grading industry also creates artificial scarcity through population control. When only thirty PSA 10 examples exist for a particular card, regardless of how many ungraded mint copies sit in collections, the graded population becomes the effective supply. Collectors focus on certified populations rather than total populations, creating market dynamics based on perceived rather than absolute scarcity.

Social Proof & Herd Behavior

Humans are social creatures who look to others when making decisions under uncertainty. This tendency manifests powerfully in the baseball card market through social proof – the phenomenon where people assume the actions of others reflect correct behavior. When collectors see others pursuing certain cards or players, they infer value and follow suit.

The 2020-2021 card market boom illustrated herd behavior on a massive scale. As prices rose and media coverage increased, new collectors entered the market in waves, driving prices higher and attracting more attention. This feedback loop created a speculative frenzy where collectors bought cards not for enjoyment but because everyone else was buying. Fear of missing out (FOMO) overpowered rational valuation.

Social media amplifies these effects. When influencers showcase massive pulls or sales, their followers respond predictably, chasing the same cards and players. This behavior creates short-term price spikes that eventually correct, but in the moment, social proof convinces collectors that rising prices validate quality. Understanding this bias helps collectors distinguish between genuine long-term value and temporary enthusiasm driven by social dynamics.

The Gambler’s Fallacy & Sunk Costs

The gambler’s fallacy – the mistaken belief that past events affect future probabilities in independent events – manifests in card collecting through box and case breaking. A collector who opens nine packs without a hit believes the tenth pack must contain something valuable. Probability doesn’t work this way. Each pack carries independent odds, but the human brain struggles to internalize this reality.

This cognitive error leads collectors to spend more money chasing variance than rational analysis would support. The excitement of potentially pulling a valuable card overwhelms statistical understanding. Card manufacturers design products to exploit this tendency, creating pack odds and configurations that maximize the psychological reward structure while maintaining profit margins.

Sunk cost fallacy presents another common trap. Collectors continue investing in collections, players, or sets because they’ve already invested significantly, even when evidence suggests they should pivot. A collector who spent $5,000 assembling a complete rainbow of a player’s parallels may continue buying new releases to “complete” the collection, ignoring that the player’s career or market dynamics have changed. Recognizing sunk costs as irrelevant to future decisions helps collectors make rational choices based on current conditions rather than past investments.

Market Timing & Momentum

Asset markets exhibit momentum – the tendency for prices that are rising to continue rising in the short term, and vice versa. Baseball card values follow similar patterns, creating both opportunities and risks for collectors. Understanding momentum helps explain why cards that seem overvalued continue appreciating while undervalued cards often remain cheap longer than logic suggests.

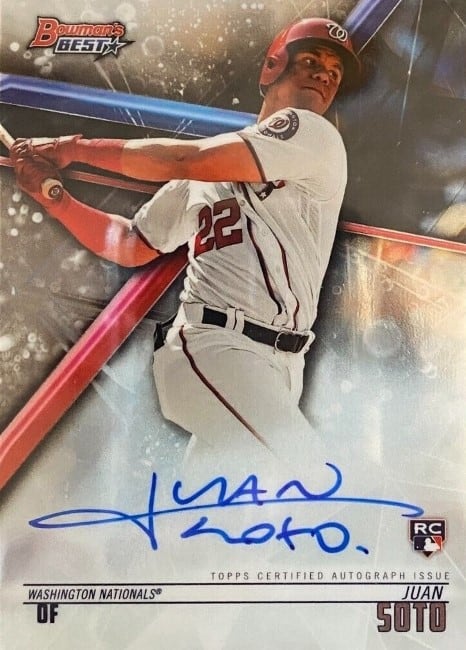

Young players with strong rookie seasons often experience price momentum that exceeds their statistical performance. Juan Soto’s rookie cards surged in 2018-2019, carrying momentum that pushed prices beyond what his (admittedly excellent) numbers alone justified. Collectors extrapolated his early success, creating demand that fed on itself. Momentum eventually reverses, but timing that reversal remains difficult.

Contrarian collectors can profit by recognizing when momentum has pushed prices too far in either direction. However, catching falling knives – buying cards in decline hoping for reversal – requires careful analysis. A player entering decline due to age or injury represents a different situation than a star experiencing temporary price correction during broader market weakness. Distinguishing between these scenarios separates successful collectors from those who accumulate depreciating assets.

Information Asymmetry & Market Efficiency

Economic theory suggests that efficient markets incorporate all available information into prices. The baseball card market exhibits varying degrees of efficiency depending on card type and visibility. Mainstream rookie cards of star players trade in relatively efficient markets where information spreads quickly and prices adjust rapidly. Obscure inserts, regional issues, or cards from secondary players often trade in inefficient markets with significant information asymmetry.

Information asymmetry creates opportunities for knowledgeable collectors. Someone who recognizes that a player’s cards are undervalued relative to their statistics or future prospects can accumulate before the broader market catches up. However, information advantages are temporary. As data becomes more accessible and collectors grow more sophisticated, market efficiency improves and arbitrage opportunities narrow.

The rise of price tracking tools, population reports, and social media has accelerated information flow in the hobby. Deals that would have persisted for weeks or months in previous decades now disappear in hours. This increased efficiency benefits the market overall by reducing transaction costs and improving price discovery, but it also means collectors must work harder to identify value.

The Role of Nostalgia & Emotional Value

Pure economic models struggle to account for emotional and nostalgic value, yet these factors powerfully influence baseball card prices. Collectors pay premiums for cards that connect to childhood memories, hometown heroes, or personal baseball experiences. This emotional component creates market inefficiencies that rational economic analysis cannot fully explain.

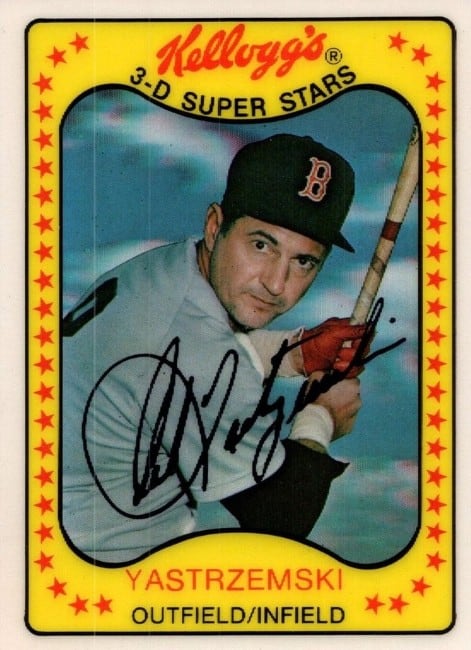

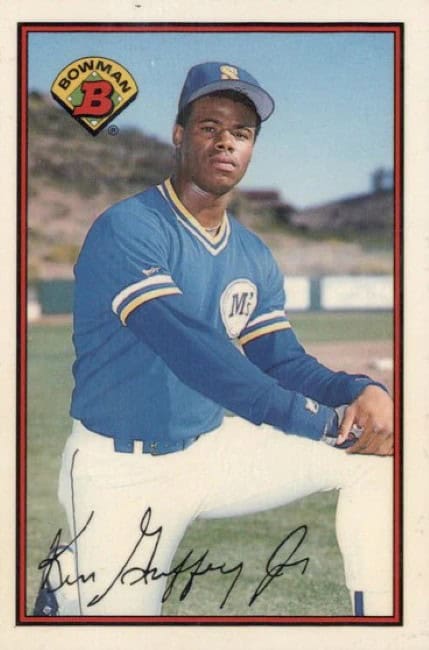

Generation X collectors who grew up during the 1980s drove demand for cards from that era beyond what condition or scarcity alone would justify. Ken Griffey Jr. cards command premiums partly because Griffey represents baseball childhood for millions of collectors. This nostalgia premium should theoretically diminish over time, but human psychology doesn’t always cooperate with economic theory.

Smart collectors recognize nostalgia as a legitimate value component rather than dismiss it as irrational. Cards that trigger emotional responses command higher prices because they provide utility beyond financial returns. A collector willing to pay $500 for a card worth $300 “objectively” isn’t necessarily making a mistake if that card provides $200 worth of personal satisfaction. The challenge lies in distinguishing personal emotional value from market value when buying and selling.

Future Scarcity & Speculative Value

Baseball card valuation requires forecasting future scarcity and demand – an inherently speculative exercise. Rookie cards trade based on expectations about career trajectories that won’t play out for years or decades. This forward-looking aspect introduces risk and opportunity simultaneously.

Collectors who correctly identify future stars early can realize substantial returns. Those who bought Mike Trout rookies in 2011-2012 before he established himself as a generational talent now hold cards worth multiples of their original purchase prices. However, for every Trout there are dozens of highly touted prospects who never pan out. Joey Gallo, Rusney Castillo, and countless others demonstrate the risk inherent in speculative collecting.

The skill lies in probability assessment rather than certainty. Successful collectors don’t need to be right about every prospect – they need an edge in identifying talent and understanding which players the market has correctly or incorrectly priced. This requires combining baseball knowledge with economic thinking about supply, demand, and human behavior patterns.

Conclusion

Baseball card values emerge from a complex interplay of economic principles and human psychology that creates one of the most fascinating collectibles markets in existence. Scarcity drives value, whether manufactured by modern companies or created over decades through attrition and condition rarity. But scarcity alone doesn’t determine prices – psychological biases like loss aversion, anchoring, and social proof shape how collectors perceive and respond to scarcity.

Understanding these forces helps collectors navigate the market more effectively. Recognizing that the endowment effect inflates personal valuations encourages more realistic pricing. Knowing that anchoring affects perception helps collectors adjust reference points based on current market conditions rather than past prices. Awareness of herd behavior and social proof provides protection against speculative bubbles driven by momentum rather than fundamentals.

The baseball card market will continue evolving as new economic and psychological factors emerge. Technology changes how information flows and how collectors interact. Generational shifts alter which players and eras command nostalgic premiums. But the fundamental forces of scarcity and psychology will remain central to card values. Collectors who grasp these principles position themselves to make smarter decisions, whether pursuing personal enjoyment, investment returns, or both. The cardboard itself may be simple, but the forces that determine its value reveal profound truths about human nature and economic behavior.